Study shows vision-language models can’t handle queries with negation words

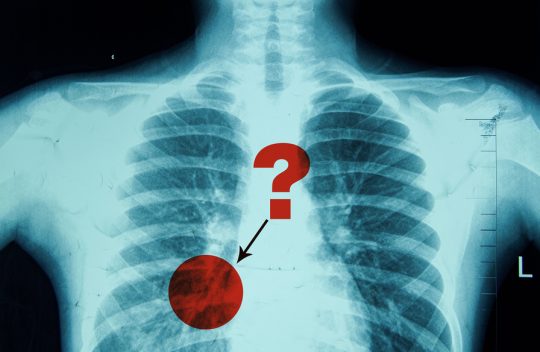

Imagine a radiologist examining a chest X-ray from a new patient. She notices the patient has swelling in the tissue but does not have an enlarged heart. Looking to speed up diagnosis, she might use a vision-language machine-learning model to search for reports from similar patients.But if the model mistakenly identifies reports with both conditions, the most likely diagnosis could be quite different: If a patient has tissue swelling and an enlarged heart, the condition is very likely to be cardiac related, but with no enlarged heart there could be several underlying causes.

In a new study, MIT researchers have found that vision-language models are extremely likely to make such a mistake in real-world situations because they don’t understand negation — words like “no” and “doesn’t” that specify what is false or absent. Learn more